KITE BODY

The Kite. Aloft. Soaring. At one, utterly, with the wind. A sheer, stretched over the lightest and simplest frame. Engined by a whisper on a breeze, skipping brightly ahead of the wind.

Breathe as the flying kite. The simple frame of the ribs, strong, yet yielding to the demands of the muscles, alternately being the breath, then sailing the resulting thermals.

Let the last four ribs, two on each side, the floaters, pull back into the planet. Like pulling down on the string directing your kite, a momentary expansion and thus deeper tension is created.

Then your legs will follow. As the tail to the kite. Entirely necessary for balance and line and direction, but not at all driving the body.

Breath-wind drives the body kite. Legs trail, graceful, without wasted effort or motion.

The body flies.

(Think about this in Footwork or Stomach Series on the Reformer )

KITE BODY – THE MECHANICS There is the tendency in exercise, and other rote activity or movement, to use certain groups of muscles for everything. Legs are consistently over-used. Consistent over-use becomes misuse of the body.

While inherent in the very discipline of pilates, conscious choice of which muscles to use is still challenging. Consistency in use is challenging. Even in pilates, the threat of overusing the thigh muscles and hip flexors prevails.

The concept of Kite Body facilitates initiating the movement from the body itself so that the legs, especially the hip flexors, do not overwork, and so that the functional breathing muscles are powerfully engaged.

Start with the simplest classic Kite.

Spine: How convenient! The backbone that runs down the length of the kite is called its spine.

Spars: The cross-bar or support sticks, which extend horizontally over the spine and out to the pointed sides of the kite are its Spars.

Skeleton : The ‘t’ or cross-shape of the connected spine and spars form the skeleton or frame of the kite and support its shape.

Sail:The light but strong fabric which covers the skeleton-frame and catches the wind, is the kite’s sail.

Feel your spine as the vertical brace in the frame, or spine, of a kite, and the width of your shoulders as the cross-bar or spar.

There is the same tensile strength, or rigidity, or support, at the ends of the frame spars as throughout each inch of the frame itself. And the frame is flat. This does not mean the spine should be cranked flat as a ruler and the shoulders ‘rigidly back, but that the end points of the shoulders are on a plane with the back, that the spine is pulled taught with the same muscle power throughout, and the same tension is created on each disk between each vertebra.

Triangles are the simplest stable shape and form. A triangle is the simplest geometric figure that will not change shape when the lengths of the sides are fixed. This cross-bracing of shoulder-line to the vertebral spine creates two triangles in the body. Pulling the ears up away from the shoulder-cross-brace creates the top triangle; pulling the tailbone down away from the shoulder-cross-brace creates an opposing triangle.

The forces in the body then, are purely tension and compression, not shearing, torsion, bending or momentum. This creates a simple, safe and powerful architecture in the body. Whereas geometrical triangles and building trusses are fairly fixed at their points, because the body is alive, you can ‘think’ the points of all of its triangles into moving farther away from all other points. The bones, then, have direction, the muscles, opposition. Opposition creates length. Your Kite Body expands.

Stretch the back and belly and neck muscles over your Kite-Body frame of the shoulders and spine and you have a flat, taut sail of living tissue with which to catch the wind, or the breath.

Kite fabric gives. Back muscles give. Sometimes too much. The back needs to be uniformly engaged for the kite to fly smoothly and elegantly. Fortunately, the muscles that help the inhale wind, (Serratus Posterior Inferior, Q. L., Latissimus Dorsi, Serratus Posterior Superior, intercostals), all live in your back. Though they themselves contract to work, their net effect is to expand the ribs, the spine and thus stretch the kite fabric. Yet more opposition. Yet more length and balance.

When there is wind (inhale), the kite body is fully taut, full of muscle potential, moving to flight. When there is not-wind (or exhale), the kite frame does not collapse or its fabric disintegrate. Neither should the body kite go flaccid. Conveniently, the muscles which facilitate the exhale include the abdominals pulling in, which helps flatten the fabric of the back.

Moving from the wind, the breath, the Kite-Body flies wide, long, uniformly integrated. The legs, then, trail the body rather than pushing it. Your legs become the long, graceful, supple tail to the

Kite-Body in flight.

Kite-Body in flight. [Box Kite description next]

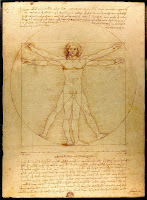

[DaVinci’s Man]